Tap to Ride: Why Transit UX Is a Mirror of Society

I’ve recently moved to Madrid, Spain to escape winter in South Africa and I’ve had to navigate the public transport system. Being the UX fanatic I am, it didn’t take long before I started thinking about the user experience of travel not just in terms of efficiency but what these systems reveal about the societies that build them.

Madrid and Johannesburg are on opposite ends of the world. One the capital of Spain, the other South Africa’s most economically powerful city. Yet despite the distance, they share some striking similarities. Both cities are magnets for internal migration and attract investment across industries. Both are vibrant cultural hubs with strong creative scenes. And both rely on public transport systems that are distinct, deeply rooted in local context, and essential to daily life. In Johannesburg, mobility largely depends on minibus taxis, buses, and the Gautrain. Madrid is supported by an extensive network of trains and buses.

This reflection focuses specifically on two core systems: the metro in Madrid and the minibus taxi network in Johannesburg. My aim is to explore how transit can act as a lens through which we understand broader societal values especially around inclusion, trust and access.

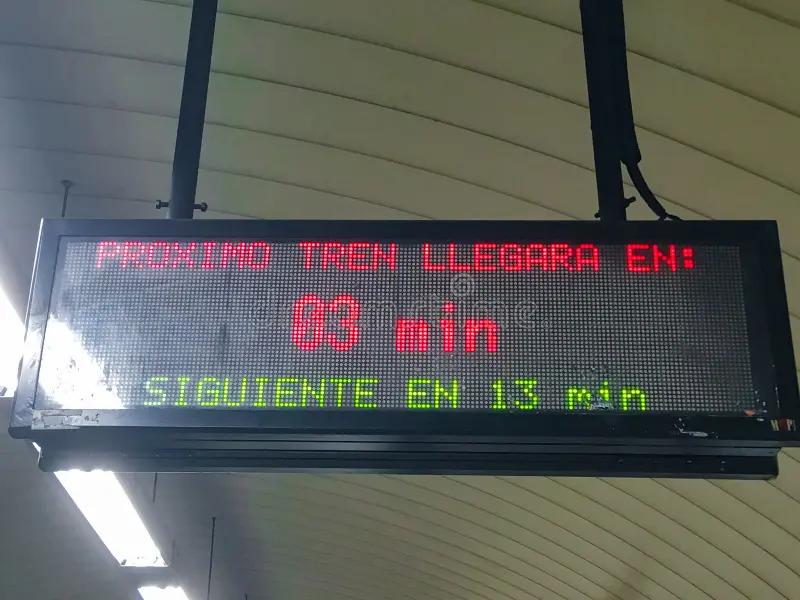

Madrid’s public transport is built with the assumption that it should be accessible to everyone. After loading your multi-ride card, you simply tap at the entrance gate and walk through. You’re greeted by digital signage displaying real-time updates. Apps like EMT Madrid and Renfe let you track buses and trains down to the minute. Even if you don’t speak Spanish, the experience is smooth. The color coded lines, signage and clear station layouts make it easy to find your way. The system is clean, punctual and simple to navigate. (Also it’s super important to note that I have travelled quite a bit in EU so this also might make the experience easier for me.) Madrid is designed around a foundation of civic trust: passengers are trusted to tap in honestly, and in return, the system is expected to function reliably.

In contrast, using Johannesburg’s mini bus taxi, (in South Africa we refer to them as just a taxi) it feels like stepping into a social codebook that no one hands you. For locals it’s second nature. For newcomers it can feel like solving a riddle. The routes aren’t listed. There are no maps or schedules. Stops are informal. You hail a taxi with a hand signal understood only by those who’ve grown up with the system. Payment is made in cash and passed forward through other passengers to the driver. There’s no digital interface to guide you the system is embedded in people, not platforms.

This contrast goes far beyond logistics. It reveals how societies define what it means to be a "user." In Madrid, the system is highly institutional: centralized and optimized for clarity. It’s a kind of UX that prioritizes independent use and strives to be self-explanatory. In Johannesburg, the UX is communal. It’s not that the system lacks design it simply wasn’t created by government or technocrats. It was created by the people who use it.

Madrid’s metro is a case study in what I’d call institutional UX: everything is standardized and legible designed to be easy for a stranger to navigate. It assumes that a good system allows any user resident or tourist to interact with it independently regardless of their background or language. That’s a design choice. It reflects a commitment to inclusion through system transparency and predictability.

Johannesburg’s taxi network represents community UX — a system that relies on interpersonal knowledge and shared behaviors. It assumes that users either already know how things work or will be taught through experience. Onboarding isn’t formalized. There’s no built-in way to learn. You learn by doing, watching and asking. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, it’s a powerful reflection of community resilience and trust among strangers. But it also makes the system difficult to access for outsiders, newcomers, or anyone who isn’t part of that collective knowledge pool.

These differences didn’t arise out of nowhere. They’re shaped by infrastructure and history. In South Africa, underinvestment in public transport, combined with a history of Apartheid and inequality meant that formal systems often excluded the very people who needed them most. The taxi network rose as a response not through state planning but through community need. It’s decentralized, agile and built to survive in an environment of minimal institutional support. The infrastructure UX is designed by the user. New comers are encouraged to learn by interacting with the current user. If you are a tourist you’ll come and go, the system is not built around the select few who are new, it is built around the majority who make use of it everyday. Many tourists or middle-class South Africans bypass the taxi system altogether, opting instead for the Gautrain or ride-hailing apps like Uber. These services are often seen as more legible and convenient, but they’re also embedded in South Africa’s class divides. Therefore the taxi system is not built for them, it is built for the active users.

In contrast Spain’s transport infrastructure reflects a very different historical trajectory. One shaped by decades of colonisation, post-war reconstruction and its long-standing membership in the European Union. Decades of coordinated public investment, access to EU infrastructure funding, and centralized governance have enabled the development of cohesive and efficient transit systems. But it’s important to recognize that this infrastructure advantage is not purely technical it’s rooted in economic and political histories that continue to shape global mobility and access today. Colonization not only enriched Europe’s urban centers but also deprived others of the same opportunity to build at scale.

That historical imbalance continues to echo in the systems we see today but acknowledging these differences doesn’t mean placing one above the other. In fact Johannesburg’s taxis reveal something profound about how people adapt when systems fail them: they create their own. The taxi network is an incredible result of social organization informal, yet effective; decentralized, yet trusted; chaotic, yet reliably functional. It shows how design doesn’t always need to be institutional to work. Sometimes, the best systems are built not on code and capital, but on cooperation and shared need.

As a UX thinker this has made me rethink my own assumptions. We often equate good UX with sleekness and efficiency. But Johannesburg’s taxis challenge that. They remind us that UX can also be relational, contextual and culturally embedded. What looks messy to one person is navigable even elegant to someone else. What looks seamless in one context may feel sterile in another.

So what can transit teach us about UX more broadly? That systems always carry assumptions. Madrid’s transport reflects a belief in universal accessibility, backed by formal structure and civic trust. Johannesburg’s taxis reflect a belief in shared responsibility, backed by community knowledge and informal collaboration.

Both systems reveal their values. One says: “You can do this on your own.” The other says: “We’ll help you along the way.”

And both are valid.

As someone moving between these worlds I feel the shift in posture. In Madrid, I’m an autonomous user. In Johannesburg, I’m part of a network. In one place I trust the system. In the other I trust the people. And that difference as a designer and researcher is incredibly instructive.

Because ultimately UX is never just about usability. It’s about the worldview a system reflects. It’s about who was imagined when the system was built and who wasn’t.

So the next time you glide through a metro gate with a tap of your card, or squint to interpret a hand signal on the side of the road, consider what those experiences are teaching you. About design. About society. About each other. And about the very different but equally meaningful ways we move through the world.